Thursday, July 28, 2005

Buster Keaton, Sherlock Jr., and Capitalism?

"You've become a cinemaphile," John Weir said to me last night after I dropped him off at his Lower East Side apartment.

And I have to admit it. I've just finished moving out, I'm packed up, ready to drive across country, and the thing I'm thinking is: I wonder what film revival house they have in Irvine?

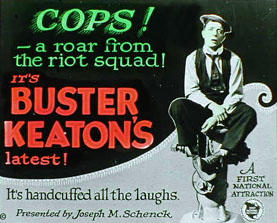

Last night's screening, at BAM- (that's the Brooklyn Academy of Music) was a Buster Keaton double bill: Cops ( a short film, I believe called a "two-reeler") and the feature, Sherlock Jr. There are so many things to say about these films. I'll start by talking about capitalism.

Ok, I admit, capitalism has been on my mind of late. I tend to rattle on about consumerism, the evil of cell phones and economies of circulation. But it was hard to overlook the commentary happening in these films.

A stunt from Cops.

Cops. The opening scene: Keaton, in a close up, is behind a set of bars, which is made to look like a jail cell. He is talking to his girlfriend, or maybe a girl he is courting. Then we get the first gag of the movie, and it's a visual one: in a medium shot, we see that it is not a jail scene, but in fact, Keaton and his amour are standing on two sides of a giant gate to her house. It's a gag, and a comment: she's in a big, expensive house, Keaton is on the outside. The social and economic separation serves to imprison Keaton. And then the dialogue flashes onto the screen. (paraphrasing here) I won't marry you until you become a successful business man.

First, I was thinking in silent films, how important dialogue becomes: because it stops the fluidity of the film, it's only used when absolutely necessary. So each line of dialogue becomes rather momentous. I'd compare it to studying a line of poetry vs. a line of fiction. Every line in poetry, when it's good, is sculpted. Well, I like to think I sculpt every line of my fiction, but when you're writing page after page, it's impossible to keep up the level of detail that you do in poetry, simply because, of the quantity factor. The same analogy works in silent movies, vs. sound. The dialogue is so restricted in silent films, it becomes all the more meaningful. So it's an important line, is what I'm saying.

Moving on. The next bit is classic vaudeville, but it's all about circulation of money: A guy is waiting for a cab, Keaton steals his wallet as the guy is getting into the cab, the guy realizes Keaton stole his wallet, goes back and takes the wallet out of Keaton's hand, but Keaton's taken the money out, the guy drives back again, gets out to fight Keaton, and Keaton gets into the

cab. The value is originally in the wallet, but the joke is, once the money is out of the wallet, the value is gone. Keaton is playing with the movement of value and money, the assumptions of where value lies, and it's very funny.

cab. The value is originally in the wallet, but the joke is, once the money is out of the wallet, the value is gone. Keaton is playing with the movement of value and money, the assumptions of where value lies, and it's very funny.Now Keaton's got some dough. Next bit: a family is moving and has all their possessions on the street, waiting for the movers. They leave the possessions unattended, and a scam artist pretends that the things are his and he's penniless and crying, and begs Keaton to buy his furniture so his kids can eat. And here's the second line of text. This time, it's Keaton's thoughts. Again, note how important the dialogue is, and I'm paraphrasing again: I'm sure to be a good business man if I buy this furniture. Keaton is satirizing the concept of ownership by reducing it to its basic principles, so much so it seems idiotic, and silly. Which in fact, it is.

The action continues: the scammer takes all Keaton's' money and leaves him a fiver. Across the street, there is a horse and carriage, a man sitting next to it, with a sign that says, $5. Keaton hands the man the bill and takes the horse. The man is confused, and when Keaton moves the horse it reveals that the sign was not for the horse, but for a coat that a shop was selling. The man holds the fiver in confusion, while the shopkeep comes out, takes the five out of his hand, and gives him the coat. The man puts it on and leaves.

Phew! So, Keaton buys property with capital that he stole, from someone who doesn't own it. So does Keaton in fact own it now? Debatable. Then the action repeats: Keaton buys a horse from someone who doesn't own it either, and in turn, that man buys a jacket with Keaton's stolen money, a jacket he didn't even want, but once it was offered to him, he wears. Money, value, and ownership are all circulating, with the rules obviously in flux and not fixed.

Keaton, though, is still just looking to make his sweetheart happy. Remember, he just wants to be married, not become a millionaire.

So, Keaton takes the cart, loads the furniture, and sets off, to be a business man? This is all the set-up for the fantastic chase scene. Keaton stumbles upon a police march- every cop you can imagine is in attendance. And, how timely: there's a terrorist! A guy throws a bomb of a roof, and it lands in Keaton's lap. He lights his cigarette off it, and then when he realizes what it is, he throws it into the crowd of cops. So, Keaton is his misguided search for love through business, has unwittingly become a terrorist. The chase scene begins.

And this a format which is set-up for both Cops and Sherlock Jr. A build up, filled with commentary and overtones, and then a big chase scene, with a series of complicated tricks, stunts, and slapstick exchanges, each one masterful, virtuosic, which rides the film to its ending.

Tomorrow: Part II of my Keaton capitalist analysis- focused on Sherlock Jr.

And even still to come: My match made in cinema heaven, Buster Keaton and Marilyn Monroe.